Edited by Steve Erdmann

**********

************

From the unbelievable to the undeniable: Epistemological pluralism, or how conspiracy theorists legitimate their extraordinary truth claims

Jaron Harambam, Stef AupersFirst Published December 17, 2019 Research Articlehttps://doi.org/10.1177/1367549419886045

Abstract

Despite their stigma, conspiracy theories are hugely popular today and have pervaded mainstream culture. Increasingly, such theories expanded into large master schemes of deceit where ‘everything is connected’. Moving beyond discussions of their truthfulness, we study in this article how such ‘super conspiracy theories’ are made plausible. We strategically selected the case study of David Icke – a true celebrity in conspiracy circles and main proponent of such all-encompassing narratives – to analyze his discursive strategies of legitimation: How does he support and validate his extraordinary claims? It is our argument that Icke succeeds by exploiting multiple sources of epistemic authority; he draws eclectically on ‘experience’, ‘tradition’, ‘futuristic imageries’, ‘science’ and ‘social theory’ to convince his audience. In a Western culture without any full monopoly on truth, and for a people wary of mainstream authorities, it proves opportune to draw on a wide variety of epistemic sources when claiming knowledge.Keywords Conspiracy theories, David Icke, epistemic authority, epistemological pluralism, New Age, postmodernism

Introduction

Conspiracy theories about the ‘real truth’ behind the attacks of 9/11, the deaths of JFK or Bin Laden, or those about the ‘true reasons’ behind vaccination campaigns, are widespread in contemporary Western culture and feature in films like The Matrix, bestsellers like The Da Vinci Code or TV series like The X-Files, 24 or Homeland. While assessments of their current popularity are hard to substantiate, especially from a historical perspective, it is clear that conspiracy theories do not operate at the margins of society; they are a mainstream and hugely popular cultural phenomenon and receive much public attention today (Knight, 2000; Melley, 2000).

In academia, however, conspiracy theories are often refuted as ungrounded and irrational speculation (Aupers, 2012; Harambam, 2017). According to critical scholars, conspiracy theorists make ‘the characteristic paranoid leap into fantasy’ – particularly because they connect many unrelated facts and events (Hofstadter, 1996 [1966]: 11). They may base their theories on (some) factual claims but go ‘wrong by locating causal relationships where none exist’ (Pipes, 1997: 31) and hence ‘inhabit a different epistemic universe, where the usual rules for determining truth and falsity do not apply’ (Barkun, 2006: 187). Conspiracy theorists, then, construct explanatory narratives that our mainstream epistemic institutions and advocates (most notably science and scientists) regard as unwarranted (Byford, 2011; Harambam and Aupers, 2015; Keeley, 1999). Today, this ‘unlawful’ connecting of seemingly unrelated dots in a meta-narrative is a phenomenon writ large. Barkun (2006) speaks in this respect of the increasing popularity of ‘super conspiracies’ or ‘conspiratorial constructs in which multiple conspiracies are believed to be linked together hierarchically’ (p. 6). Knight (2000) identifies a similar development: ‘over the last decades conspiracy theories have shown signs of increasing complexity and inclusiveness, as once separate suspicions are welded into Grand Unified Theories of Everything’ (p. 204).

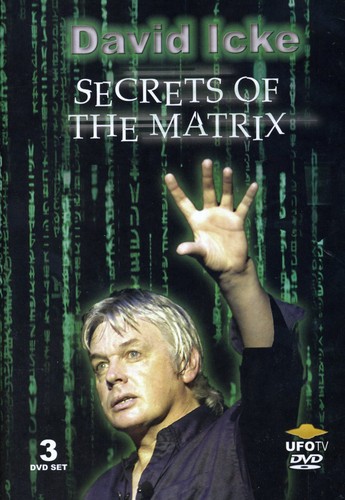

Moving beyond discussions of their truthfulness, we study from a cultural sociological perspective how these all-encompassing super conspiracy theories are made plausible. Drawing everything together is easy, making people believe what you say is more difficult. And yet millions of people around the world – and many in the Dutch conspiracy milieu – are attracted by them. One of the main and most popular propagators of such all-encompassing narratives of deceit is David Icke (Barkun, 2006: 103). He is most famous – or notorious – for his ‘reptilian thesis’: the idea that ‘reptilian human-alien hybrids are in covert control of the planet’ (Robertson, 2013: 28). But he is also known for his ‘synthesis’ of seemingly different or ‘antithetical’ thought: he brings together New Age teachings with apocalyptic conspiracy theories about a coming totalitarian New World Order (cf. Barkun, 2006; Ward and Voas, 2011). As Lewis and Kahn (2005) rightfully note, ‘Icke’s greatest strength is his totalizing ambition to weave numerous sub-theories into an extraordinary narrative that is both all-inclusive and all-accounting’ (p. 8). More specifically, Robertson (2016) argues that this is the result of ‘an epistemology that acknowledges [different] sources of access to knowledge’ (p. 9). Alongside the common appeals to ‘science’ and ‘tradition’, Robertson (2016) argues, conspiracy theorists like David Icke draw on other less acknowledged ‘epistemic strategies’ as well: ‘appeals to experiential, channeled and synthetic knowledge’ (p. 10).

Robertson (2016) points here to an important aspect of the epistemic authority of conspiracy theorists: they can draw on ‘the full range of epistemic strategies’ (p. 25), while today’s dominant epistemic institutions only allow appeals to ‘science’ (Gieryn, 1999). Robertson (2016) provides a sophisticated and thorough analysis of the lives and works of several ‘millennial conspiracists’ (such as David Icke) and shows that they (strategically) draw on various epistemic strategies in order to gain authority in this cultural milieu. Basing ourselves on Icke’s 2011 ‘performance’ in Amsterdam, we take this lead further and systematically analyze in full empirical detail how David Icke actually draws on such a multitude of epistemic sources. We focus on his discursive strategies of legitimation and pose open research questions: How does he support and validate his extraordinary claims in order to achieve epistemic authority in the conspiracy milieu? What are the main epistemic strategies he deploys? And what proofs, tropes and metaphors underpin each of these analytically distinct epistemic strategies?

Claiming epistemic authority

Many different scholars – from Hofstadter (1996 [1966]: 29) to Knight (2000: 204) and Barkun (2006: 3) – claim that the adage ‘everything is connected’ is ‘one of the guiding principles in virtually every conspiracy theory’. While Knight (2000) makes a plea for the rationality of this adage in a world of global relations (pp. 204–241), the majority of scholars hold this ‘unifying quality’ of contemporary conspiracy theories to be their major epistemological flaw (e.g. Barkun, 2006; Byford, 2011; Hofstadter, 1996 [1966]; Keeley, 1999; Popper, 2013 [1945]). They argue that conspiracies may be ‘typical social phenomena’ (Popper, 2013 [1945]) 307), but ‘these need to be recognized as multiple, and in most instances unrelated events which cannot be reduced to a single, common denominator’ (Byford, 2011: 33, original emphasis). To ‘regard a “vast” or “gigantic” conspiracy as the motive force in historical events’ (Hofstadter, 1996 [1966]: 29) is therefore simply ludicrous: social life is inextricably more complex (Barkun, 2006: 7).

Yet such ‘grand unified theories of everything’ are immensely popular today. They are present in the ideas of people consuming conspiracy theories, they are visualized in colorful diagrams that are circulated on conspiracy websites and they form the thought of major conspiracy theorists, like David Icke. Connecting the dots between loose ends may, for such scholars, involve the notorious ‘big leap from the undeniable to the unbelievable’ (Hofstadter, 1996 [1966]: 38), but for many people in the conspiracy milieu, these connections are very plausible and real. What critical scholars of conspiracy theories seem to gloss over in their dedication to debunk conspiracy theories, then is the fact that these overarching theories need to be made plausible if such conspiracy theorists are to have any serious attention. People are not passive or gullible believers; they need to be actively convinced. Underlying conspiracy theorists’ efforts to connect the seemingly unrelated is a need for epistemic validation: they want their claims on truth to be believed, after all. But such ‘grand unified theories of everything’ are not your everyday news: the world as we know it is often turned upside down and inside out, connecting the most outlandish ideas to the very ordinary experiences of people. Indeed, it often is the ‘unbelievable’ that is sold here. The question is therefore how do conspiracy theorists convincingly do so?

To approach this issue, we need to move beyond the positivistic reflex to debunk conspiracy theories as unfounded and irrational (Barkun, 2006; Byford, 2011; Hofstadter, 1996 [1966]; Keeley, 1999; Popper, 2013 [1945]) and adopt a cultural sociological approach. From this perspective, there are multiple ways to support truth claims. Max Weber (2013 [1922]) already pointed out that one can claim authority through charisma, tradition or, in modern societies, particularly through rationalized procedures like science or law. In our Western world, referencing to ‘science’ – its institutions, experts, epistemologies and methods – is perhaps the most prevalent and powerful way to lend credibility to the claims one is making (Brown, 2009). ‘If “science” says so, we are more often than not inclined to believe it or act on it – and prefer it over claims lacking this epistemic seal of approval’ (Gieryn, 1999: 1). The tremendous epistemic authority ‘science’ enjoys today is, however, not uncontested: trust in ‘science’, particularly its institutions and experts, gradually declined over the last decades in most Western countries (cf. Beck, 1992; Inglehart, 1997) and other forms of knowledge are on the rise. Examples are alternative and complementary medicine, all kinds of non-science-based nutritional regimes and New Age philosophies of life (cf. Campbell, 2007; Hammer, 2004; Heelas, 1996). Conspiracy culture is part of this cultural trend turning away from mainstream epistemic authorities. Not only do conspiracy theorists openly challenge the epistemic authority of science (Harambam and Aupers, 2015), but like David Icke himself, they often advance other ways of knowing as more authentic and authoritative (e.g. Robertson, 2016). Icke is therefore not just the archetype of the contemporary ‘super conspiracy theorist’ (cf. Barkun, 2006: 8; Knight, 2000: 204), but a typical exponent of the broader cultural movement discontented with mainstream epistemic institutions and their scientific-materialist worldview (e.g. Campbell, 2007; Heelas, 1996; Roszak, 1995). Now, how does Icke draw on multiple epistemic strategies to make his rather extravagant ideas seem plausible?

Method, data and analysis

The empirical material used for this analysis was collected on the day Icke held his show – ‘Human Race, Get Off Your Knees. The Lion Sleeps No More’ – in Amsterdam on 10 December 2011. This event was one of the many places the first author included in his ‘multi-sited ethnography’ (Falzon, 2009) of the Dutch ‘conspiracy milieu’ (Harambam, 2017). For a period of 20 months, between October 2011 and June 2013, extensive visits were made to their social gatherings – shows, political manifestations, conferences and movie screenings – and to their private homes. Besides the traditional ethnographic methods of participant observation and interviewing, the first author undertook content analyses of the media (videos, texts, cartoons, etc.) circulated at these places and on the Internet (their own websites, blogs, Facebook pages, etc.).

In this article, however, we will mostly draw on that particular performance of David Icke. Given the fact that Icke is exemplary of this new stream of conspiracy culture (Barkun, 2006; Knight, 2000; Robertson, 2013), the analysis of his performance is a strategic case study (cf. Flyvbjerg, 2006) to research in empirical detail how the extraordinary claims of super conspiracy theories are made plausible. The first author participated as one of the many attendees of Icke’s show and observed not only his performance but also his audience with whom he spoke during that day and invited for further conversation elsewhere. He made field notes of Icke’s performance – its textual contents and his manifestations as an artist – and of the (reactions of the) public. Although these field notes were – as ‘thick descriptions’ (Geertz, 1973) – valuable for the research at large, they lacked the precision needed to adequately substantiate our claims in this article. We hence complemented the field notes with an analysis of professional video recordings of the same show at two different places, respectively, in London’s Wembley Arena show on 27 October 2012 and London’s Brixton Academy in May 2010. The videos are for sale on his website, but also feature on YouTube for free. We have therefore chosen to use these video recordings as the source for the precise quotations used in this article. The first author has re-examined this show a few times with a theoretical focus on the rhetorical and epistemological strategies used by Icke to legitimate his truth claims. The analysis is therefore more textual than ethnographic. Each successive time different themes were fine-tuned to inductively arrive at a typology (cf. Glaser and Strauss, 1967). All excerpts are from the YouTube film1 and are easily accessed. We have consistently marked each quote by its time location on the video.

‘The Day That Will Change Your Life’: David Icke in Amsterdam

David Icke is a true conspiracy celebrity; he holds performances in large venues all over the world, attracting crowds of thousands.2 He is also a writer of more than 20 books, which are read in 12 different languages, and he owns a popular website with many videos and interviews, and a rather active discussion platform (more than 100,000 registered users).3 David Icke manages to bring together a diverse range of people (Barkun, 2006; Ward and Voas, 2011). As Lewis and Kahn (2005) argue, ‘Icke appeals equally to bohemian hipsters and right-wing reactionary fanatics [who] are just as likely to be sitting next to a 60-something UFO buff, a Nuwaubian, a Posadist, a Raëlian, or New Age earth goddess’ (p. 3). His fan base is quite diverse: from new religious movements to political anarchists and from alternative healers to anti-government militants on the extreme right. All of them, however, share a discontent with our current societal order, and more precisely with the way our epistemic institutions (i.e. science, politics, religion, media, etc.) work.

This counts for his 2011 Amsterdam performance in the auditorium of the RAI convention center as well. David Icke has attracted a 1500 plus crowd who have paid for a €69 ticket to see him speak today. It is a full day’s program: from 10:00 in the morning until 7:00 in the evening, David Icke will ‘put all the puzzles pieces together’ (13.30). The show opens when we see on the huge video screen on stage a chain of connected iron links passing while we hear a gloomy and grim music increasing in intensity. The links are chained around the earth and have texts on them: ‘New World Order’, ‘Rothschild Zionism’, ‘Child Abuse’, ‘Babylonian Brotherhood’, ‘Bilderbergers’, ‘Aspartame’, ‘Religion’, ‘Club of Rome’, ‘Chemtrails’, ‘Fluoride’, ‘HAARP’, ‘Satanism’, ‘Trilateral Commission’, ‘Mainstream Media’, ‘Fabian Society’, ‘Intelligence agencies’, ‘IMF’, ‘World Army’, ‘Police State’, ‘Global Politics’, ‘Big Pharma’, ‘War on Terror’, ‘Vaccines’, ‘Tavistock’, ‘Military/Industrial Complex’, ‘War on Drugs’, ‘Mind Control’. They make up one large interconnecting chain. And as the music turns more and more ominous, we see a lion – with the image of the earth projected on its skin – bound in chains. The music reaches its dramatic climax as the lion breaks out of his bondage and while he growls loudly, we see the links flying over the screen. The message is clear: the lion sleeps no more, the world liberates itself. And the audience is ready to receive David Icke with an overwhelming applause: the conspiracy rock star is finally here.

In the next 9 hours, David Icke elaborates passionately about ‘the multi-levelled conspiracy to enslave humanity in a global concentration camp’ (15:30). In general, Icke distinguishes between ‘the five-sense level of this conspiracy’ and those levels that transcend the here and now. The former is mostly about the corruption and dogmatism of our modern institutions – media, science, politics, religion and so on – and how they manipulate us and ‘program our minds’ into acquiescence (19:00–25:00). Icke integrates all these institutions in one pyramid. At the top of this pyramid, we find a network of secret societies and powerful families, sometimes captured under the header of the ‘Illuminati bloodlines’ and at other times called ‘Rothschild Zionists’. But, as Icke explains, ‘there is this other-dimensional, non-human, level to look at’ (1:41:00). We now get to the ‘reptilian thesis’ through which Icke gained his fame and notoriety (Barkun, 2006: 105). Icke explains that his super conspiracy theory ‘involves non-human entities that take a reptilian form [which] manipulate this reality through interbreeding bloodlines’ (1:44:00). These are the Illuminati-hybrid family networks that rule the world. However normal they may look to us – Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, Queen Elizabeth – they are in fact ‘shapeshifting’ reptilians ‘hiding behind human form’ (2:07:00). Icke sketches a pristine image of a forgotten past when people still lived in harmony with the natural world and were connected to higher levels of consciousness, but argues that ‘the road to tyranny began when these reptilians arrived here’ (2:23:00). Part of ‘this reptilian intervention’ was to change our DNA so that we can no longer access the world beyond our five senses: ‘they want to lock humanity in that prison’ (3:27:30).

And that, Icke concludes, is ‘the bottom line of this conspiracy: controlling our perception of what is real’ (3:18:00). Our institutions – media, science, politics, religion – play an important part in making these ‘prisons for our minds’ (19:00–25:00), but Icke points to another method of mind control: ‘the moon-matrix’. He argues that the moon is actually a hollowed-out planetoid brought here by these reptilian entities that emits a frequency that distorts our interpretation of reality (2:30:00–3:08:00). However, change is coming, Icke ends optimistically: ‘a new epoch of enlightenment and expansion, of love, harmony and respect is moving into human experience’ (5:12:00). But ‘to go down this road of freedom, we first need to free our minds from the programming of a lifetime’ (22:00); we need ‘to remove the barriers of belief and perception that keep us from enlightenment’ (5:27:00). ‘Enough!’, Icke shouts loudly while he ends the show, ‘it is time to fly! It is time to fly . . .’ (6:42:00). And given the massive applause Icke receives, his audience seems ready for it.

David Icke brings together different conspiracy theories into one dazzling, yet cohesive narrative which captures his audience for hours. In the following section, we will show on which sources of epistemic authority he draws to make his conspiracy theory of everything plausible.

‘Just Following the Clues’: appealing to experience

One of the ways Icke lends legitimacy to his super conspiracy is by reference to his own personal experience, or life course. Virtually, the first thing he does when opening his show is giving a snapshot of ‘the chain of events that had led to now’ (6:30). He explains,

when I look back, I can see very clearly in my life, what happens to all of us, you go through a series of experiences and they seem to be random, they don’t seem to be connected. But when you look back, you see it’s a journey of connected synchronistic experiences that are leading us in a certain direction. (06:00)

Like the opening scene of the chained lion, David Icke makes it clear that ‘everything is connected’ on a personal level as well. He tells us how he was a professional soccer player having to deal with rheumatoid arthritis, how he went into television: ‘what that did was show me the inside of media: shite’, and that he got into (green party) politics: ‘and I saw politics from the inside: how it’s just a game’ (08:00). When he claims that the global elites are actually shapeshifting reptilians, he supports that with his own experience of meeting former UK Prime Minister Ted Heath in television studio years ago. And ‘as I looked into his eyes it was like looking into two black holes, it was like looking through him into this other dimension where he is really controlled from’ (2:06:30). Icke supports his personal experiences with those of others, friends, family or just people he has met: ‘so I met this lady in Canada some years ago, a very power-dressing business women, [who] had this experience and she was shaking when she told me the story’ (3:05:00). Basically, she told Icke how she had a boyfriend who one night while having sex turned ‘totally reptilian and then morphed back to human. And these bizarre stories, have been told by people from all over the world, people from all walks of life’ (3:07:00).

But there is another, more supernatural, type of experience on which Icke draws. He explains how his life changed dramatically after seeing a psychic to have hands on healing for his arthritis. She channels him visions of how he ‘was going out on a world stage to reveal great secrets, that there was a shadow over the world to be lifted, there was a story that had to be told’ (09:30). And although ‘this sounded like complete bloody craziness’ to Icke, his ‘life started to change’ after going to a mountain in Peru where he had ‘extraordinary experiences’ (10:00). This changed everything:

suddenly concepts, information, perceptions, were pouring into my mind. I was seeing the world in a different way, and I was asking the big questions: who are we? where are we? and why is the world as it is? And from that time the puzzle pieces started to be handed to me in amazingly synchronistic ways. (12.00)

Like a true prophet, Icke receives the wisdom he wrote down in his books from the gods above or from a metaphysical master plan: ‘the path is already mapped out, you only have to follow the clues’ (12:30). And that is what Icke has done: ‘all the information was coming to me in incredible synchronicity, of meeting people, seeing documents, coming across information, having experiences. [. . .] just following the clues, I came across this reptilian connection to the families that are running our reality’ (17:00). This Jungian concept of synchronicity or ‘meaningful coincidences’ is prevalent in Icke’s explanations of how he has gained his spiritual wisdom during his life course. By actively ‘putting the puzzle pieces together’ (13.30) or ‘connecting the dots’ (15:00) between seemingly unrelated experiences, he accumulated knowledge about the real reality underneath the surface of everyday life.

Such ‘revelatory experiences in which spokespersons claim to have gained privileged insight into those spiritual truths they present in their texts’ (Hammer, 2004: 369) have been an important source of epistemic authority in various historical religious traditions, but are also used by contemporary ‘prophets’ in today’s market of New Age spiritualities (Heelas, 1996). Icke blends mundane and supernatural experiences together and actively synthesizes that into a larger narrative which obtains a deeper meaning. Whereas Robertson (2016) differentiates ‘channeling’ from the epistemic strategy of ‘experience’, we argue, as we have shown here, that they are intimately connected (pp. 49–53). Icke’s appeal to the epistemic authority of ‘experience’, then, resonates with a broader cultural trend in which the ‘inner’ self and personal experience is the most trustworthy source of knowledge (e.g. Aupers and Houtman, 2006; Heelas, 1996; Van Zoonen, 2012).

‘All Across the Ancient World’: appealing to tradition

Another important part of David Icke’s argumentation is based on the (allegedly) perennial wisdom of ancient cultures. Icke supports his claims throughout his show by referring to the myths of African tribes, the sagas of Asian emperors, the dreams of Native-American shamans and the more familiar Abrahamic narratives. The best example is Icke’s reptilian thesis. He starts by showing an excerpt from the Old Testament (Genesis, 6:4) but argues that ‘that’s just the biblical version, all across the ancient world you see similar stories and accounts of this interbreeding’ (1:48:30). The most prominent symbolization of this reptilian interbreeding is visible, Icke argues, in the worship of ‘the serpent gods’ which happens all across the world, in all cultures, and in all religions. He starts off by saying that ‘the oldest form of religious worship in the world has been taken back 70.000 years, to an area of the Kalahari desert in South Africa and it is the worship of the serpent or worship of the snake’ (2:07:30). He gives many more examples: ‘Chinese emperors used to claim the right to be emperor because of their genetic connection to the serpent gods. And this is a theme all across the world between the serpent gods and royalty’ (1:58:00). He continues with myths of the old Mesopotamia, the Egyptians (‘who have their pharaohs represented as an cobra’), in Japan and Asia (‘the dragon is the most dominant symbol of that world’), in central and south America (‘the Mayan “Kukulkan” and “Quetzalcoatl” of the Aztecs’), the old druids, ‘folklore is full of serpents, and the Zulu Chitauri’ – their mythical ‘children of the serpent’ (2:07:00–2:10:00). But symbols of the serpent gods are also prominent in contemporary life, Icke tells us: in our myths, fairytales, the emblems of the aristocracy, the logos of car companies: ‘it’s amazing how many times you see the symbols of reptiles and humans, or part human, part reptile, overseeing the palaces, castles and churches of this elite’ (2:17:00). His conclusion is clear: ‘all worship the serpent gods’ (2:10:00).

However, ‘something else goes parallel with the reptilian story’, Icke tells us:

Again not just in the bible with the Garden of Eden, but all across the ancient accounts is the reptilian connection and the Fall of Men. And this is universal. The ancient accounts all talk about a time when humans were so unbelievably different to how we are today. (1:48:30)

He starts off by saying that ‘the energetic schism’ was

of course symbolized by Noah and the great flood. And Noah is simply a biblical version of much older stories that tell exactly the same story of how the earth turned over, how there were great geological catastrophes and how humans lost their power of the connection they had to higher levels of consciousness. (2:24:30)

In his legitimation of the Fall of Men through reptilians, Icke jumps from religious books, to popular myth, to fiction. As to the latter, he quotes large pieces of the book of Carlos Castaneda – a famous, but fictitious anthropological study – which supports virtually his whole thesis of how ‘predators from the depths of the cosmos took over the rule of our lives’ (3:10:00).

Throughout his show, then, Icke appeals to the knowledge and wisdom of the ‘ancient world’ to support and validate his own theories: if ‘they’ have been saying it for thousands of years, it must be true. In a (counter)culture wary of modern institutions and the knowledge they produce, this makes good sense: these old traditions represent after all a more authentic and pure base of wisdom than the cold rationality of modern science (Heelas, 1996; Roszak, 1995). Icke’s appeal to the ancient cultures is what Hammer (2004) identifies as the epistemological strategy of ‘tradition’: basing one’s truth claims in the source of non-European (spiritual) lore. Such appeals are by no means references to ‘actual’ practices, customs and beliefs of ‘ancient cultures’, but construct a radically ‘modern’ reinterpretation of non-European tales and traditions (Hammer, 2004: 23). Icke similarly takes such (fictional) legends then as (containing) factual truths. Whether these are ‘really’ true or not may be less relevant for him and his audience: such ancient cultures simply ‘possessed a vast wisdom, a spirituality lost to us’ (Hammer, 2004: 136). David Icke conveniently draws on this more widely felt sentiment of modern cultural discontent and his appeal to ‘tradition’ falls on fertile ground in the conspiracy milieu.

‘Living in the Cosmic Internet’: appealing to futuristic imageries

In contrast to supporting one’s claims by appealing the wisdom of our ‘ancient cultures’, Icke also looks to the ‘future’ as a source of authority when he invokes the imageries brought to life by science fiction and digital technologies. To begin with the latter, Icke speaks, for example, about our bodies as computers: ‘our DNA is like a universal software code’, ‘just like computers, we have a phenomenal anti-virus system we call the human immune system’, and ‘what we call cultures are different sub-softwares of the human software’ (1:10:00–1:12:30). These analogies should all add plausibility to Icke’s argument that our bodies decode a universal energy field (the metaphysical universe) and herewith bring the reality we experience every day into being. Icke: ‘it is just like the wireless internet, where you get a computer and pull the whole world wide web, a whole collection of reality, out of the unseen, to appear on a screen, anywhere in the world’ (36:30). And there are more of such references to digital technologies that should support his ideas. For example, when Icke explains why our reality feels and appears ‘real’, it is ‘because we are living in a virtual reality universe. A fantastically advanced version of a gigantic computer game’ (32:30). Or he points to the new digital technologies that have made moving three-dimensional (3D) holographs possible, like news readers in a television show or Michael Jackson appearing on stage long after his death: ‘some of these digital holograms look so solid’, Icke explains, that ‘people are afraid to walk through them. And that’s what this is, digital holograms is the reality we’re experiencing’ (1:24:30). These examples of the ‘realness’ of virtual realities are deployed by Icke to convince us of his understanding that ‘we live in a very advanced equivalent of the holographic internet, we live in the cosmic internet’ (40:30).

The futuristic imageries developed in science fiction provide another source for Icke to tap into when supporting his super conspiracy theory. He particularly refers to The Matrix throughout his show (e.g. 42:00/47:00/2:59:00). The main idea put forward in that movie – that we all live, without really knowing it, in an artificial non-existent simulated world – resonates quite well with Icke’s worldview. It is a powerful metaphor to convince his audience. When he speaks about how reality is an illusion created inside our heads, he brings us to ‘this scene from The Matrix – which is absolutely right – where the Neo character says, “but this isn’t real!” And Morpheus says ‘well, what is real? How do you define real? If you’re talking about what you can feel, what you can smell, taste and see, then “real” is simply electronic signals interpreted by your brain’. That’s all it is’, Icke affirms. But the appeal to science fiction goes further than The Matrix. Icke supports, for example, his claim that the moon is an alien instrument of mind control by referencing to Star Wars – ‘in a galaxy far far away. . . I don’t think so. This is much closer at home’ (2:48:00) – and John Carpenter’s They Live – ‘I thought it was symbolically accurate when I first saw it, but now I know it’s unbelievably accurate’ (3:02:00). Whereas the former movie features the Death Star ‘in the same bloody way as I am talking about the moon’ (2:49:00), the latter boasts a TV tower transmitting a frequency – like the moon-matrix – ‘which is preventing the population from seeing what they would normally see [the truth]’ (3:05:00). Both movies confirm what Icke is saying all along.

What was science fiction yesterday is often science faction today. And vice versa, newly introduced technologies feed the social imagination about its ‘magical possibilities’. The introduction of the telegraph in the 19th century, for instance, motivated the public discourse on ‘spirit communication’ and supported the plausibility and popularity of Spiritism (Stolov, 2008). In his performance, Icke plays with this social imagination about digital technologies to convince the audience. He argues, ‘so much of science fiction ain’t fiction at all, they’re getting it from facts’ (2:51:00) and, consequentially, that much more ‘unbelievable’ stuff has potential reality. Barkun (2006) states that this ‘fact-fiction reversal’ is common: ‘conspiracy literature is replete with instances in which fictional products are asserted to be accurate factual representations of reality’ (p. 29). In a society where people are exposed to technologically real, yet virtual ‘miracles’ on a daily basis – from games to virtual reality (VR) and artificial intelligence (AI) – Icke’s outlandish notion of the cosmic Internet gains in plausibility.

‘What Scientists Are Saying’: appealing to science

In a time and place dominated by the scientific worldview like ours, anyone trying to legitimize their claims on reality would do well to base it in ‘science’ (cf. Gieryn, 1999). It is therefore no surprise that David Icke does abundantly so. The first time Icke alludes to ‘science’ is by using it as ‘building blocks’ of his own theories. When he is arguing, for example, that the moon is actually a hollowed-out planetoid from outer space, he quotes many different scientists to support his claim. He begins with scientists who question the common understandings of the moon as our earth’s satellite: ‘Isaac Asimov, a Russian professor of Biochemistry’ and ‘Irwin Shapiro from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics’ both argue that given its size and position, the moon cannot be there (2:36:00). He continues with scientists from NASA who concluded after seismic experiments that ‘the moon is more like a hollow than a homogenous sphere’ (2:36:30) – findings that were supported by ‘Dr. Frank Press and Dr. Sean Solomon from MIT’ (2:37:00). To argue that the moon is a construct from outer space, Icke extensively quotes ‘two scientists from the Russian Academy of Science’ – Michael Vahsin and Alexander Shcherbakov – who ‘wrote an article in Sputnik Magazine titled: “Is the moon the creation of alien intelligence?”’ (2:38:00). After presenting their findings, Icke advances their marvelous conclusion:

they say it’s a hollowed out planetoid! ‘What we have here is a very ancient spaceship, the interior of which was filled with [. . .] everything necessary to enable this caravel of the universe to serve as Noah’s ark of intelligence’. (2:40:00)

Icke’s efforts here should give his audience the impression that his theory of the moon as a hollowed-out planetoid is not just something he is imagining, it is actually supported by real scientists.

But David Icke also alludes to ‘science’ as ‘stepping stones’ to reach his own more extravagant ideas. He starts in such cases from a position of scientific quandary and then advances his own rather extraordinary thoughts where science leaves matters unexplained. For example, when Icke explains that our ‘body-computer’ can no longer reach higher levels of consciousness, he turns to unresolved matters in astronomy and goes from there:

the range of frequencies our body-computer can decode is extraordinarily tiny. We are virtually blind, in terms of [seeing] what exist. The vast majority of this universe is what scientists call dark energy or dark matter and they call it dark not because it’s pitch black, but because we cannot decode it. Therefore it’s not within our realm of experience. We have to work it out by its impact on things we can see. (59:00)

In such cases, ‘science’ is the base camp from which Icke ventures into the unexplored territories ‘science’ dares not to enter. They may point in the right direction, Icke says, but because ‘they’re focusing on their own discipline, their own individual dots, and they don’t connect the dots, they can’t see the picture!’ (1:26:00).

Icke finally draws on ‘science’ for its rich repertoire of cultural imageries to make his thoughts clear and intelligible. So when he is talking about how ‘ethereal reptilian entities’ are actually controlling people like Obama and Queen Elisabeth, Icke turns to the image of the sterile laboratory:

and this is a good analogy, you know, when these scientists in a laboratory are working with something they can’t touch because it’s too dangerous. What they are working with will be in a tank, and they’ll put gloves on, which allows them to be outside the tank, but to manipulate inside the tank. Well, that is a very good symbol of what I am talking about, these illuminati bloodlines, these hybrid bloodlines operate like with those gloves, operating inside this reality. (1:56:00)

Or somewhat later in his show when Icke is talking about how the ‘control system’ has trained us into acquiescence and obedience, he puts forward the image of a classical conditioning experiment:

it is a mind game. More and more fine details of our life are being dictated. It is to turn us into a version of this [we see picture of a mouse in the middle of a maze]. When you put shock equipment down different channels [the mouse learns where not to go]. And what they are doing is [the same]: giving us punishments for doing this, punishments for doing that, so we become subservient to the system, never challenge it. (5:00:00)

‘Science’, to conclude, is an important part of our cultural imaginary, and Icke draws effortlessly from it to make his ideas intelligible.

Despite the critique on the institution of science, appeals to its epistemic authority remain highly effective to lend credibility to knowledge (e.g. Gieryn, 1999). Even ‘spokespersons for religious outlooks’ need to position themselves in one way or another to the dominant scientific worldview (Hammer, 2004: 202). Icke taps extensively on ‘science’ to legitimize his claims. On one hand, it functions as his positive Other when he argues that ‘scientists are saying the same’. But ‘science’ also functions in Icke’s thought as its negative Other – when it is the signpost of limitation (as in its inability to provide answers to the mysteries of black holes, dark matter and junk DNA), ‘look, I dare to go further’. Just like religious spokespersons in the esoteric tradition (Hammer, 2004: 201–206; Robertson, 2016: 48–49), Icke uses the authority of ‘science’ pragmatically in the legitimization of his ideas.

‘The Incessant Centralization of Power’: appealing to (critical) social theory

When Icke comes back from exploring the multidimensional level of his super conspiracy to explain ‘how it all plays out in this five sense reality’ (3:27:00); he mostly draws on notions developed in the social sciences. His main question ‘how do a few control the many?’ is unequivocally answered in sociological terms: by ‘the way they have structured society’ (3:27:30).

This allusion to social theory is particularly clear when Icke explains that ‘when you are the few and you have to control the many, you have to centralize decision-making’ (3:36:00). He sketches a pyramidal view of society with the centralization of power/knowledge as its organizing principle:

the idea is to hold advanced knowledge in the upper levels of this structure, where a few at the top are the only ones who know how it all fits together, and they keep the general population in ignorance of what they know, therefore they have the power to manipulate the masses. (3:28:00)

Knowledge is power, Icke explains after Foucault. Very much akin to sociological understandings of modern societies, Icke’s ‘pyramid of manipulation’ is also hierarchically structured along ‘the major institutions that affect our daily life’: religion, finance, military, education, politics and so on (see Figure 1). Through this pyramidal view of society, he underscores the rationality of functionally differentiating society in order to most efficiently control it – thoughts reminiscent of Weber’s (2013 [1922]) bureaucratization theories. Especially, by emphasizing how such systems operate through hierarchical structures, where lower level ‘officials’ just ‘do their job’ and ‘follow the rules’ (cf. Arendt, 2006 [1963]), Icke argues how society can be manipulated with the cooperation of those being manipulated:

they [just] go to work, earn money, go on holiday, they don’t try to manipulate anybody, they don’t try to create a Fascist Orwellian totalitarian. But they don’t know how their apparently innocent contribution individually connects with other apparently innocent contributions around the system. And that’s how they keep what’s going on in the hands of the few. (3:30:00)

Figure 1. David Icke’s pyramid of manipulation.

There is a clear legacy of Marxian thought here that is apparent when compared to ‘The Pyramid of the Capitalist System’ (Figure 2) – a satiric cartoon image published in a 1911 edition of Industrial Worker. Although the dominant institutions may have somewhat changed, the message is similar:

humans have been put in this circular lifestyle, just a repeating cycle of work, eat, sleep and work, eat, sleep . . . so that we spend so much time surviving and not lift our head up to see what’s going on. (3:35:30)

Figure 2. Pyramid of capitalist system.

Meanwhile, the ruling classes enjoy their privileges, while the major institutions guarantee order and stability. Even the operating logic is similar: just ‘follow the money’ and you will get to the cabal. The affinity with Marxian thought, however, goes further. Icke speaks about how these institutions ‘program us with a certain perception of reality which we carry through our lives so we will be good little slaves’ (22:30). Not a far cry from how the ‘superstructure of society’ maintains and legitimizes the dominant ‘relations of production’ by advancing them as normal, just and legitimate (Marx and Engels, 1965 [1865]). Ultimately, Icke reiterates Gramscian notions of how these institutions – and especially the education system – socialize people to obediently serve in their designated (labor)roles in society: ‘which is why the education system is not about educating, it’s about programming’ (3:28:00). These acquired ‘hegemonic beliefs’, Gramsci argues, thwart critical thought and ultimately obstruct ‘revolution’ (e.g. 2011). For the same reasons, Icke urges us to ‘free our minds’ because the ‘control system has been set up in endless ways to divert us, to confuse us and to keep us from the understanding that would set us free’ (14:00). But there is a way out, Icke tells us in rather Marxist terms, ‘the choice is to become conscious!’ (25:00). Class conscious?

When Icke speaks about the centralization of power, he also provides a form of historical sociology. He explains how we

started with tribal situations as part of this centralization process. The tribes came together in what we call nations, nations under unions, like the European Union. And the next stage of that, which they are already preparing for, is to take us into a world government. (3:37:00)

This notion of a coming totalitarian world government, or New World Order, is central to many conspiracy theories (e.g. Barkun, 2006; Byford, 2011). What is crucial here, however, is that Icke gives a socio-historical explanation of how we got into the ‘centralized dictatorship the EU is now’ (3:43:00). So when Icke refers to ‘globalization’ as part of the strategy of the cabal, his explanation mimics those sociological theories standing in the tradition of Wallerstein’s ‘World-Systems Analysis’:

globalization is the constant centralization of power, more and more power in the hands of a few, more and more, the globalized economy is making every country dependent on every other country, therefore has no power of individual action and decision making [. . .] and the reason they want to do this is because dependency equals control. (3:45:30)

In contrast to the appeals to ‘science’ where Icke literally quotes natural scientists, the reference to social scientific knowledge is less explicit. But the way Icke explains our current situation and how we got there shows an elective affinity with sociological analysis, especially of the critical or (neo)Marxist signature. In doing so, Icke unmistakably draws authority from explanations that originate in the social sciences, but are now widespread. His talk testifies to the trickling down of (social) scientific notions in wider society (Giddens, 1984). Critical social theory has become a popular idiom for conspiracy theorists to express their discontent with our current societal order.

Conclusion

David Icke brings the heavens and the earths together in one master narrative of institutional mind control, multidimensional universes and shapeshifting reptilian races. This is his objective because ‘when you connect the dots, suddenly the light goes on and the picture forms’ (15:00). We have shown in this article how Icke draws on a multitude of sources of epistemic authority to convince his audience that the ‘unbelievable’ is indeed ‘undeniable’. His claims to truth are a hodgepodge of epistemological strategies: he draws on personal experience, perennial narratives in ancient cultures, technological imageries, science and critical social theory to support his super conspiracy theory. (Academic) criticasters of conspiracy theorists may find this eclecticism problematic: they deplore how such ‘charlatans’ unsettle the boundaries between fact and fiction and warn for the societal ramifications of such relativism (e.g. Barkun, 2006; Pipes, 1997; Sunstein and Vermeule, 2009). But debunking these conspiracy theories as irrational and problematic does not help us in understanding its massive appeal and plausibility from a cultural perspective. Based on our analysis, we argue in line with Robertson (2016) that Icke’s epistemological pluralism adds plausibility to his super conspiracy theory. Moving beyond a strict religious studies perspective, however, our analysis identified two more distinct epistemic strategies: ‘futuristic imageries’ and ‘(critical) social theory’. Alluding to technological advances and science fiction helps people imagine the ‘unbelievable’, while referring to the societal critiques of academics gives credence to their societal discontents. These are important contemporary additions to Hammer’s (2004) tri-partite schema of drawing on ‘tradition’, ‘science’ and ‘experience’ when claiming knowledge outside the orthodox mainstream. In short, Icke is able to convince his audience of his super conspiracy theory and acquire epistemic authority in the conspiracy milieu precisely because he is able to deploy a very diverse range of epistemic strategies, from the spiritual to the (social) scientific and from the visceral to the cerebral. We will develop two sociological explanations as to why this is the case – hypotheses about the cultural reception of super conspiracy theories that suggest new routes for further research. First of all, in contemporary Western culture, no belief system has a full monopoly on truth – particularly since the erosion of Christian tradition, doctrine and beliefs are not necessarily and fully replaced by the epistemic authority of modern science (Beck, 1992; Brown, 2009; Inglehart, 1997). For people wary of mainstream institutions and their truth claims, it proves opportune to draw on a wide variety of epistemic sources when claiming knowledge. Motivated by a generalized distrust, they assemble different perspectives on truth and ‘pick-and-mix’ from both established and ‘stigmatized knowledge’ (cf. Barkun, 2006: 26; Campbell, 2007; Lyon, 2000; Possamai, 2005). However, Icke’s eclecticism may not only serve the epistemological omnivores, his super conspiracy theory may also appeal to distinctly different social groups, coming from different subcultures and lifestyles. Scholars have pointed to the fact that he manages to bring together a diverse range of people, from leftist spiritual seekers to right-wing reactionaries (Barkun, 2006; Lewis and Kahn, 2005; Ward and Voas, 2011), and our own observations and interviews in the field corroborate that (Harambam and Aupers, 2017). Our second suggestion, then, is that Icke’s reliance on multiple epistemic sources of authority attracts distinctly different audiences: both those attracted to New Age spiritualities, and amateur-scientists, social activists, hackers and fans of the science fiction genre. His text is highly ‘polysemic’: each follower can ‘decode’ Icke’s super conspiracy theory differently and in conformity with one’s own social identity and political interests.

Whether Icke’s theories address the epistemological omnivores – individuals combining experience, (social)science and ancient myth to ‘find the truth’ – or different social groups with distinct epistemological preferences (or both) need to be further researched. In addition, a venue for further research is the communal dimension of conspiracy culture (Ibid.). Icke’s show, after all, is a form of counter-cultural entertainment, and there are many facets of collective effervescence at work during his performances (Durkheim, 1965 [1912]). For now we conclude that Icke’s fusion of science and religion, fact and value, folklore and futurism is reminiscent of what many scholars identify as postmodern culture (cf. Best and Kellner, 1997; Jameson, 1991). The dissolution of stable categories of knowledge, the ‘bricolage’ and ‘pastiche’ of many different cultural forms and the individualistic possibilities for interpretation are features that have found their way from the arts and intelligentsia to everyday life of ordinary citizens, like those attending Icke’s show. Postmodernism may be dead in academia; it is alive and kicking in the outside world.

Authors’ note

Jaron Harambam is now affiliated with KU Leuven, Belgium.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This article is based on research funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) and is part of the project ‘Conspiracy Culture in the Netherlands: Modernity and Its discontents’, file number 404-10-438.

ORCID iD

Stef Aupers  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8286-7147

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8286-7147

Notes

1.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O2vlegEBuO0, last retrieved on 27 February 2015.

2.This was one of the slogans David Icke promoted his show with, for example, http://www.purityevents.nl/david-icke-the-lion-sleeps-no-more, last retrieved on 15 February 2016.

3.http://www.davidicke.com, last retrieved on 7 May 2015.

References

| Arendt, H (2006 [1963]) Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. London: Penguin Books. Google Scholar | |

| Aupers, S (2012) ‘Trust No One’: Modernization, paranoia and conspiracy culture. European Journal of Communication 26(4): 22–34. Google Scholar | SAGE Journals | ISI | |

| Aupers, S, Houtman, D (2006) Beyond the spiritual supermarket: The social and public significance of New Age spirituality. Journal of Contemporary Religion 21(2): 201–222. Google Scholar | Crossref | |

| Barkun, M (2006) A Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Google Scholar | |

| Beck, U (1992) Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage. Google Scholar | |

| Best, S, Kellner, D (1997) The Postmodern Turn. London: Guilford Press. Google Scholar | |

| Brown, TL (2009) Imperfect Oracle: The Epistemic and Moral Authority of Science. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. Google Scholar | |

| Byford, J (2011) Conspiracy Theories: A Critical Introduction. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. Google Scholar | Crossref | |

| Campbell, C (2007) Easternization of the West: A Thematic Account of Cultural Change in the Modern Era. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers. Google Scholar | |

| Durkheim (1965 [1912]) The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. New York: Free Press. Google Scholar | |

| Falzon, MA (ed.) (2009) Multi-Sited Ethnography: Theory, Practice and Locality in Contemporary Research. Farnham: Ashgate. Google Scholar | |

| Flyvbjerg, B (2006) Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry 12(2): 219–245. Google Scholar | SAGE Journals | ISI | |

| Geertz, C (1973) The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York: Basic Books. Google Scholar | |

| Giddens, A (1984) The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Berkely, CA: University of California Press. Google Scholar | |

| Gieryn, TF (1999) Cultural Boundaries of Science: Credibility on the Line. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. Google Scholar | |

| Glaser, BG, Strauss, AL (1967) The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: Aldine. Google Scholar | |

| Gramsci, A (2011) Prison Notebooks, vol. 1–3. New York: Columbia University Press. Google Scholar | |

| Hammer, O (2004) Claiming Knowledge: Strategies of Epistemology from Theosophy to the New Age. Leiden: Brill. Google Scholar | |

| Harambam, J (2017) The Truth is Out There: Conspiracy Culture in an Age of Epistemic Instability. Unpublished Dissertation, Erasmus University Rotterdam. Google Scholar | |

| Harambam, J, Aupers, S (2015) Contesting epistemic authority: Conspiracy theories on the boundaries of science. The Public Understanding of Science 24(4): 466–480. Google Scholar | SAGE Journals | ISI | |

| Harambam, J, Aupers, S (2017) I am not a conspiracy theorist: Relational identifications in the dutch conspiracy milieu. Cultural Sociology 11(1): 113–129. Google Scholar | SAGE Journals | ISI | |

| Heelas, P (1996) The New Age Movement. Oxford: Blackwell. Google Scholar | |

| Hofstadter, R (1996 [1966]) The Paranoid Style in American Politics and Other Essays. New York: Knopf. Google Scholar | |

| Inglehart, R (1997) Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Google Scholar | Crossref | |

| Jameson, F (1991) Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. London: Verso Books. Google Scholar | |

| Keeley, BL (1999) Of conspiracy theories. The Journal of Philosophy 96(3): 109–126. Google Scholar | Crossref | ISI | |

| Knight, P (2000) Conspiracy Culture: From Kennedy to the X-Files. New York: Routledge. Google Scholar | |

| Lewis, T, Kahn, R (2005) The reptoid hypothesis: Utopian and dystopian representational motifs in David Icke’s alien conspiracy theory. Utopian Studies 16(1): 45–74. Google Scholar | |

| Lyon, D (2000) Jesus in Disneyland: Religion in Postmodern Times. Cambridge: Polity Press. Google Scholar | |

| Marx, K, Engels, F (1965 [1865]) The German Ideology. London: Lawrence & Wishart. Google Scholar | |

| Melley, T (2000) Empire of Conspiracy: The Culture of Paranoia in Postwar America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Google Scholar | |

| Pipes, D (1997) Conspiracy: How the Paranoid Style Flourishes and Where It Comes from. New York: The Free Press. Google Scholar | |

| Popper, KR (2013 [1945]) The Open Society and Its Enemies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Google Scholar | Crossref | |

| Possamai, A (2005) Religion and Popular Culture: A Hyper-Real Testament. Brussels: Peter Lang. Google Scholar | Crossref | |

| Robertson, DG (2013) David Icke’s reptilian thesis and the development of New Age theodicy. International Journal for the Study of New Religions 4(1): 27–47. Google Scholar | Crossref | |

| Robertson, DG (2016) UFOs, Conspiracy Theories and the New Age: Millennial Conspiracism. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. Google Scholar | |

| Roszak, T (1995) The Making of a Counter Culture: Reflections on the Technocratic Society and Its Youthful Opposition. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. Google Scholar | |

| Stolov, J (2008) Salvation by electricity. In: de Vries, H (ed.) Religion: Beyond a Concept. New York: Fordham University Press, pp.668–687. Google Scholar | |

| Sunstein, CR, Vermeule, A (2009) Conspiracy theories: Causes and cures. The Journal of Political Philosophy 17(2): 202–227. Google Scholar | Crossref | ISI | |

| Van Zoonen, L (2012) I-pistemology: Changing truth claims in popular and political culture. European Journal of Communication 27(1): 56–67. Google Scholar | SAGE Journals | ISI | |

| Ward, C, Voas, D (2011) The emergence of conspirituality. Journal of Contemporary Religion 26(1): 103–121. Google Scholar | Crossref | |

| Weber, M (2013 [1922]) Economy and Society. Berkely, CA: University of California Press. Google Scholar |

Biographical note

Jaron Harambam is an interdisciplinary trained sociologist working on news, disinformation and conspiracy theories in today’s agorithmically structured media ecosystem. He received his PhD in Sociology (highest distinction) from Erasmus University Rotterdam, held postdoctoral research positions at the Institute for Information Law (IViR) at the University of Amsterdam, and is now a Marie Sklodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship holder at the Institute for media Studies at Leuven University.

Stef Aupers is cultural sociologist and works as a professor media culture at the Institute for Media Studies at Leuven University. He published widely on the mediatization of religion, spirituality and conspiracy theories and, particularly, computer game culture.

**********

David Icke

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaJump to navigationJump to search

| David Icke | |

|---|---|

| Icke in 2013 | |

| Born | David Vaughan Icke 29 April 1952 (age 69) Leicester, England |

| Occupation | Conspiracy theorist,[1] former sports broadcaster and football player |

| Movement | New Age conspiracism |

| Association football careerPosition(s)GoalkeeperYouth career1967–1971Coventry CitySenior career*YearsTeamApps(Gls)1971–1973Hereford United[2]37(0)* Senior club appearances and goals counted for the domestic league only | |

| Website | davidicke.com |

David Vaughan Icke (/ˈdeɪvɪd vɔːn aɪk/; born 29 April 1952) is an English conspiracy theorist and a former footballer and sports broadcaster.[1][3][4][5][6] He has written over 20 books, self-published since the mid-1990s, and spoken in more than 25 countries.[7][8][9]

In 1990, he visited a psychic who told him he was on Earth for a purpose and would receive messages from the spirit world.[10] This led him to state in 1991 he was a “Son of the Godhead”[6] and that the world would soon be devastated by tidal waves and earthquakes, predictions he repeated on the BBC show Wogan.[11][12] His appearance led to public ridicule.[13] Books Icke wrote over the next 11 years developed his world view of New Age conspiracism.[14] His endorsement of an antisemitic forgery, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, in The Robots’ Rebellion (1994) and And the Truth Shall Set You Free (1995) led his publisher to stop handling his books, which were then self-published.[9]

Icke believes the universe to consist of “vibrational” energy and infinite dimensions sharing the same space.[15][16][17] He claims an inter-dimensional race of reptilian beings, the Archons or Anunnaki, have hijacked the Earth and a genetically modified human–Archon hybrid race of shape-shifting reptilians – the Babylonian Brotherhood, Illuminati or “elite” – manipulate events to keep humans in fear, so that the Archons can feed off the resulting “negative energy”.[15][18][19][20] He claims many public figures belong to the Babylonian Brotherhood and propel humanity towards a global fascist state or New World Order, a post-truth era ending freedom of speech.[14][15][21][22] He sees the only way to defeat such “Archontic” influence is for people to wake up to the truth and fill their hearts with love.[15] Critics have accused Icke of being antisemitic and a Holocaust denier with his theories of reptilians serving as a deliberate “code”.[23][24][25] Icke denies these claims.[26]

Contents

- 1Early life, family and education

- 2First marriage

- 3Journalism, sports broadcasting

- 4Green Party, Betty Shine

- 5Turquoise period

- 6Writing and lecturing

- 7Conspiracy theories

- 8Reception

- 9Selected works

- 10See also

- 11References

- 12External links

Early life, family and education

The middle son of three boys born seven years apart, Icke was born in Leicester General Hospital to Beric Vaughan Icke and Barbara J. Icke, née Cooke, who were married in Leicester in 1951. Beric Icke served in the Royal Air Force as a medical orderly during World War II,[27] and after the war became a clerk in the Gents clock factory. The family lived in a terraced house on Lead Street in the centre of Leicester,[28] an area that was demolished in the mid-1950s as part of the city’s slum clearance.[29] When David Icke was three, around 1955, they moved to the Goodwood estate, one of the council estates the post-war Labour government built. “To say we were skint,” he wrote in 1993, “is like saying it is a little chilly at the North Pole.”[28] He recalls having to hide under a window or chair when the councilman came for the rent; after knocking, the rent man would walk around the house peering through windows. His mother never explained that it was about the rent; she just told Icke to hide. He wrote in 2003 that he still gets a fright when someone knocks on the door.[30]

Icke attended Whitehall Infant School, and then Whitehall Junior School.[31][30]

Football

Icke has said he made no effort at school, but when he was nine he was chosen for the junior school’s third-year football team. He writes that this was the first time he had succeeded at anything, and he came to see football as his way out of poverty. He played in goal, which he wrote suited the loner in him and gave him a sense of living on the edge between hero and villain.[32]

After failing his 11-plus exam in 1963, he was sent to the city’s Crown Hills Secondary Modern (rather than the local grammar school), where he was given a trial for the Leicester Boys Under-14 team.[33] He left school at 15 after being talent-spotted by Coventry City, who signed him up in 1967 as their youth team’s goalkeeper. In 1968 he played in the Coventry City youth team that were runners up to Burnley in the F.A. Youth Cup. He also played for Oxford United‘s reserve team and Northampton Town, on loan from Coventry.[34]

Rheumatoid arthritis in his left knee, which spread to the right knee, ankles, elbows, wrists and hands, stopped him from making a career out of football. Despite stating that he was often in agony during training, Icke managed to play part-time for Hereford United, including in the first team when they were in the fourth, and later in the third, division of the English Football League.[35] But in 1973, at the age of 21, the pain in his joints became so severe that he was forced to retire.[36]

First marriage

Icke met his first wife, Linda Atherton, in May 1971 at a dance at the Chesford Grange Hotel near Leamington Spa, Warwickshire. Shortly after they met, Icke left home following one of a number of frequent arguments he had started having with his father. His father was upset that Icke’s arthritis was interfering with his football career. Icke moved into a bedsit and worked in a travel agency, travelling to Hereford twice a week in the evenings to play football.[37]

Icke and Atherton married on 30 September 1971, four months after they met.[38] Their daughter was born in March 1975, followed by one son in December 1981, and another in November 1992.[39] The couple divorced in 2001 but remained friends, and Atherton continued to work as Icke’s business manager.[40]

Journalism, sports broadcasting

The loss of Icke’s position with Hereford meant that he and his wife had to sell their home, and for several weeks they lived apart, each moving in with their parents. In 1973 Icke found a job as a reporter with the weekly Leicester Advertiser, through a contact who was a sports editor at the Daily Mail.[41] He moved on to the Leicester News Agency, did some work for BBC Radio Leicester as its football reporter,[42] then worked his way up through the Loughborough Monitor, the Leicester Mercury and BRMB Radio in Birmingham.[43]

In 1976, Icke worked for two months in Saudi Arabia, helping with the national football team. His position at the team was planned to be a longer term position, but Icke decided to stay in the UK after his first holiday back.[44] After his return to the UK, BRMB decided to give him his job back, after which he successfully applied to Midlands Today at the BBC’s Pebble Mill Studios in Birmingham, a job that included on-air appearances.[45] One of the earliest stories he covered there was the murder of Carl Bridgewater, the paperboy shot during a robbery in 1978.[46]

In 1981, Icke became a sports presenter for the BBC’s national programme Newsnight, which had begun the previous year. Two years later, on 17 January 1983, he appeared on the first edition of the BBC’s Breakfast Time, British television’s first national breakfast show, and presented the sports news there until 1985. In 1983 he co-hosted Grandstand, at the time the BBC’s flagship national sports programme.[47] He also published his first book that year, It’s a Tough Game, Son!, about how to break into football.[48]

Icke and his family moved in 1982 to Ryde on the Isle of Wight.[49] His relationship with Grandstand was short-lived. He wrote that a new editor arrived in 1983 who appeared not to like him, but he continued working for BBC Sport until 1990, often on bowls and snooker programmes, and at the 1988 Summer Olympics.[50] Icke was by then a household name, but has said that a career in television began to lose its appeal to him; he found television workers insecure, shallow and sometimes vicious.[51]

In August 1990, his contract with the BBC was terminated when he initially refused to pay the Community Charge (also known as the “poll tax”), a local tax Margaret Thatcher‘s government introduced that year. He ultimately paid it, but his announcement that he was willing to go to prison rather than pay prompted the BBC, by charter an impartial public-service broadcaster, to distance itself from him.[52][53]

Green Party, Betty Shine

Icke moved to Ryde on the Isle of Wight in 1982.

Icke began to flirt with alternative medicine and New Age philosophies in the 1980s in an effort to relieve his arthritis, and this encouraged his interest in Green politics. He joined the Green Party and became a national spokesperson within six months.[54] His second book, It Doesn’t Have To Be Like This, an outline of his views on the environment, was published in 1989.

Icke wrote that 1989 was a time of considerable personal despair, and it was during this period that he said he began to feel a presence around him.[55] He often describes how he felt it while alone in a hotel room in March 1990, and finally asked, “If there is anybody here, will you please contact me because you are driving me up the wall!” Days later, in a newsagent’s shop in Ryde, he felt a force pull his feet to the ground and heard a voice guide him toward some books. One of them was Mind to Mind (1989) by Betty Shine, a psychic healer in Brighton. He read the book, then wrote to her requesting a consultation about his arthritis.[56][57][54][58]

Icke visited Shine four times. During the third meeting, on 29 March 1990, Icke claims to have felt something like a spider’s web on his face, and Shine told him she had a message from Wang Ye Lee of the spirit world.[59][60] Icke had been sent to heal the earth, she said, and would become famous but would face opposition. The spirit world was going to pass ideas to him, which he would speak about to others. He would write five books in three years; in 20 years a new flying machine would allow us to go wherever we wanted and time would have no meaning; and there would be earthquakes in unusual places, because the inner earth was being destabilised by having oil taken from under the seabed.[57][61][56]

In February 1991, Icke visited a pre-Inca Sillustani burial ground near Puno, Peru, where he felt drawn to a particular circle of waist-high stones. As he stood in the circle he had two thoughts: that people would be talking about this in 100 years, and that it would be over when it rained. His body shook as though plugged into an electrical socket, he wrote, and new ideas poured into him. Then it started raining and the experience ended. He described it as the kundalini (a term from Hindu yoga) activating his chakras, or energy centres, triggering a higher level of consciousness.[62][14]

Turquoise period

Icke’s turquoise period followed an experience by a burial site in Sillustani, Peru, in 1991.

There followed what Icke called his “turquoise period”. He had been channelling for some time, he wrote, and had received a message through automatic writing that he was a “Son of the Godhead”, interpreting “Godhead” as the “Infinite Mind”.[63] He began to wear only turquoise, often a turquoise shell suit, a colour he saw as a conduit for positive energy.[64][65] He also started working on his third book, and the first of his New-Age period, The Truth Vibrations.

In August 1990, before his visit to Peru, Icke met Deborah Shaw, an English psychic based in Calgary in Alberta, Canada. When he returned from Peru they began a relationship, with the apparent blessing of Icke’s wife. In March 1991 Shaw began living with the couple, a short-lived arrangement that the press called the “turquoise triangle”. Shaw changed her name to Mari Shawsun, while Icke’s wife became Michaela, which she said was an aspect of the Archangel Michael.[66][67]

The relationship with Shaw led to the birth of a daughter in December 1991, although she and Icke had stopped seeing each other by then. Icke wrote in 1993 that he decided not to visit his daughter and had seen her only once, at Shaw’s request. Icke’s wife gave birth to the couple’s second son in November 1992.[68][69]

Green Party resignation and press conference

In March 1991, Icke resigned from the Green Party during a party conference, telling them he was about to be at the centre of “tremendous and increasing controversy”, and winning a standing ovation from delegates after the announcement.[53] A week later, shortly after his father died, Icke and his wife, Linda Atherton, along with their daughter and Deborah Shaw, held a press conference to announce that Icke was a son of the Godhead.[70][71] He told reporters the world was going to end in 1997. It would be preceded by a hurricane around the Gulf of Mexico and New Orleans, eruptions in Cuba, disruption in China, a hurricane in Derry, and an earthquake on the Isle of Arran. The information was being given to them by voices and automatic writing, he said. Los Angeles would become an island, New Zealand would disappear, and the cliffs of Kent would be underwater by Christmas.[72]

Wogan interview

The headlines following Icke’s press conference attracted requests for interviews from Nicky Campbell‘s BBC Radio One programme, for Terry Wogan‘s prime-time Wogan show, and Fern Britton‘s ITV chat show.[73]

Wogan introduced the 1991 segment with “The world as we know it is about to end”. Amid laughter from the audience, Icke demurred when asked if he was the son of God, replying that Jesus would have been laughed at too, and repeated that Britain would soon be devastated by tidal waves and earthquakes. Without these, “the Earth will cease to exist”. When Icke said laughter was the best way to remove negativity, Wogan replied of the audience: “But they’re laughing at you. They’re not laughing with you.”[73][74][75] The BBC was criticised for allowing it to go ahead; Des Christy of The Guardian called it a “media crucifixion”.[76][77]

The interview led to a difficult period for Icke. In May 1991, police were called to the couple’s home after a crowd of over 100 youths gathered outside, chanting “We want the Messiah” and “Give us a sign, David”.[78] Icke told Jon Ronson in 2001:

One of my very greatest fears as a child was being ridiculed in public. And there it was coming true. As a television presenter, I’d been respected. People come up to you in the street and shake your hand and talk to you in a respectful way. And suddenly, overnight, this was transformed into “Icke’s a nutter.” I couldn’t walk down any street in Britain without being laughed at. It was a nightmare. My children were devastated because their dad was a figure of ridicule.[65][79]

In 2006, Wogan interviewed Icke again for a special Wogan Now & Then series. Wogan was apologetic for his conduct in the 1991 interview.[80] However, in his autobiography, Mustn’t Grumble, Wogan described Icke as being a “ranting demagogue convinced we were all manipulated sheep”.[81]

Writing and lecturing

Early books

The Wogan interview separated Icke from his previous life, he wrote in 2003, although he considered it the making of him in the end, giving him the courage to develop his ideas without caring what anyone thought.[82] His book The Truth Vibrations, inspired by his experience in Peru, was published in 1991.

Between 1992 and 1994, he wrote five books, all published by mainstream publishers, four in 1993. Love Changes Everything (1992), influenced by the “channelling” work of Deborah Shaw, is a theosophical work about the origin of the planet, in which Icke writes with admiration about Jesus. Days of Decision (1993) is an 86-page summary of his interviews after the 1991 press conference; it questions the historicity of Jesus but accepts the existence of the Christ spirit. Icke’s autobiography, In the Light of Experience, was published the same year,[83] followed by Heal the World: A Do-It-Yourself Guide to Personal and Planetary Transformation (1993).

The Robots’ Rebellion

In his 2001 documentary about Icke, Jon Ronson cited this cartoon, “Rothschild” (1898), by Charles Léandre, arguing that Jews have long been depicted as lizard-like creatures who are out to control the world.[84]

Icke’s The Robots’ Rebellion (1994), a book published by Gateway, attracted allegations that his work was antisemitic. According to historian Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, the book contains “all the familiar beliefs and paranoid clichés” of the US conspiracists and militia.[85] It claims that a plan for world domination by a shadowy cabal, perhaps extraterrestrial, was laid out in The Protocols of the Elders of Zion (c. 1897).

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion is an anti-Semitic literary forgery,[86] probably written under the direction of the Russian secret police in Paris, purporting to reveal a conspiracy by the Jewish people to achieve global domination. It was exposed as a forgery in 1920 by Lucien Wolf and the following year by Philip Graves in The Times.[87] Once exposed, it disappeared from mainstream discourse until interest in it was renewed by the American far right in the 1950s.[87] Interest in it was further spread by conspiracy groups on the Internet.[88] According to Michael Barkun, Icke’s reliance on the Protocols in The Robots’ Rebellion is “the first of a number of instances in which Icke moves into the dangerous terrain of antisemitism”.[89][90]

Icke took both the extraterrestrial angle and the focus on the Protocols from Behold a Pale Horse (1991) by Milton William Cooper, who was associated with the American militia movement; chapter 15 of Cooper’s book reproduces the Protocols in full.[91][92][93] The Robots’ Rebellion refers repeatedly to the Protocols, calling them the Illuminati protocols, and defining Illuminati as the “Brotherhood elite at the top of the pyramid of secret societies world-wide”. Icke adds that the Protocols were not the work of the Jewish people, but of Zionists.[94][95]

The Robots’ Rebellion was greeted with dismay by the Green Party’s executive. Despite the controversy over the press conference and the Wogan interview, they had allowed Icke to address the party’s annual conference in 1992 – a decision that led one of its principal speakers, Sara Parkin, to resign – but after the publication of The Robot’s Rebellion they moved to ban him.[91][96][97][98][99] Icke wrote to The Guardian in September 1994 denying that The Robots’ Rebellion was anti-Semitic, and rejecting racism, sexism and prejudice of any kind, while insisting that whoever had written the Protocols “knew the game plan” for the twentieth century.[100][101]

Self-publishing

Why do we play a part in suppressing alternative information to the official line of the Second World War? How is it right that while this fierce suppression goes on, free copies of the Spielberg film, Schindler’s List, are given to schools to indoctrinate children with the unchallenged version of events. And why do we, who say we oppose tyranny and demand freedom of speech, allow people to go to prison and be vilified, and magazines to be closed down on the spot, for suggesting another version of history.— And the Truth Shall Set You Free (1995)[9]

Icke’s next manuscript, And the Truth Shall Set You Free (1995), contained a chapter questioning aspects of the Holocaust, which caused a rift with his publisher, Gateway.[95][102][23] In the book Icke suggested that Jews funded the Holocaust by quoting and seconding Gary Allen‘s claim that “The Warburgs, part of the Rothschild empire, helped finance Adolf Hitler”. In his view, schools “indoctrinate children with the unchallenged version of events” with the mainstream account of the Holocaust thanks to their use of free copies of the film Schindler’s List (1993).[103][24] After borrowing £15,000 from a friend, Icke established Bridge of Love Publications, later called David Icke Books. He self-published And the Truth Shall Set You Free and all his subsequent books.